Andrés Serbin and Andrei Serbin Pont – Crisis Cripples Venezuela

By Andrés Serbin and Andrei Serbin Pont

Published in The Courier: https://www.stanleyfoundation.org/articles.cfm?id=852

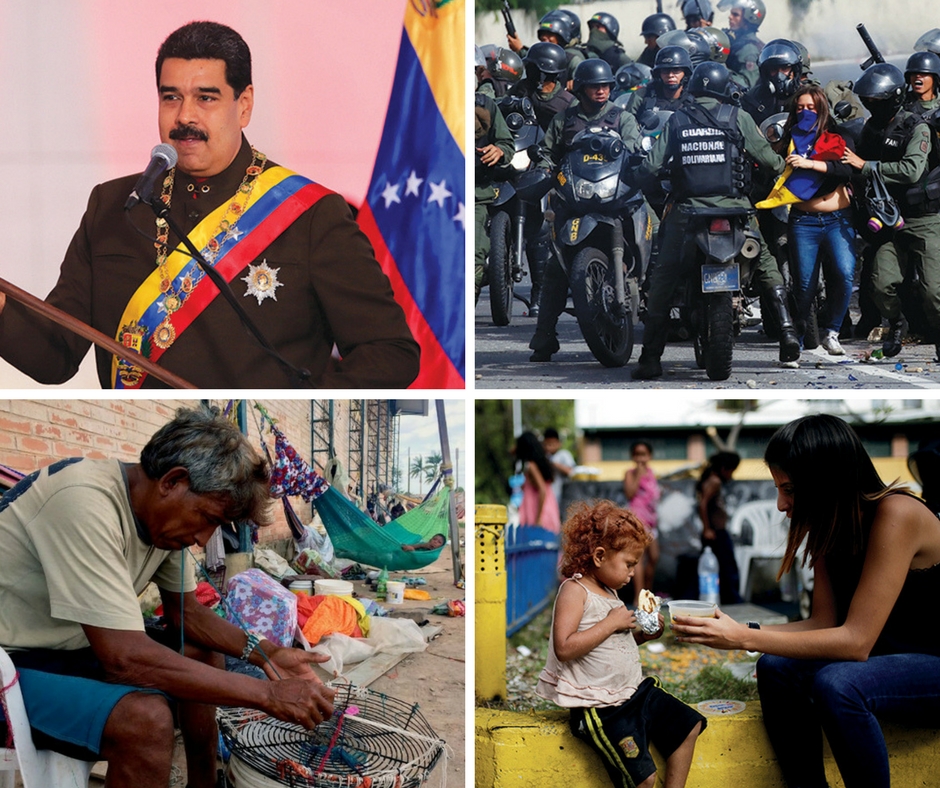

The end of the commodities boom is having a devastating impact on the Venezuelan economy. The drop in international oil prices that began toward the end of 2014 has also been accompanied by inadequate social planning, expanding state control of the economy, and skyrocketing levels of corruption and mismanagement among governmental officials and the military.

As a result, the Venezuelan economy is in shambles, corruption and violence are rampant, and the Chavismo revolutionary project launched by then-President Hugo Chávez is floundering, while the economic, political, and humanitarian crises continue to grow.

As political unrest and violence escalate in Venezuela, the health system is deteriorating, food scarcity is growing, and national institutions continue to fail to support adequate basic living conditions. According to a 2016 survey, Encuesta Sobre Condiciones de Vida en Venezuela (Survey on Living Conditions in Venezuela), poverty increased by 34 percent from 2014 to 2016, while extreme poverty increased from 24 percent in 2014 to 52 percent in 2016. The latest figures from 2017 are staggering, indicating that 82 percent of Venezuelans are living under the poverty line, the highest rate in its history and making the country one of the poorest in the region. The survey also reported roughly three in four Venezuelans have lost weight involuntarily, averaging 19 pounds per person. (See “Resources” at end.)

As people turn to the streets to protest, they are violently repressed by police, the armed forces, and paramilitary groups. Since March 2017, over 100 people have died as a result of state-led repression and hundreds of others have been imprisoned for exercising their constitutional rights, while opposition leadership is actively persecuted and imprisoned by security and paramilitary forces and intelligence services. Furthermore, human rights violations have become widespread when citizens are detained, and intelligence services have set up clandestine detention centers such as “La Tumba” (The Grave) where political dissidents are illegally kept without informing the judiciary and then isolated from any outside contact for days or weeks while being physically and psychologically tortured. Other detained civilians are subjected to speedy military trials and imprisoned in military installations.

On the streets, state-led violence is not limited to repression of violent protest, but also includes generalized targeting of entire neighborhoods considered “opposition neighborhoods.” The Venezuelan government seems not only unable but also unwilling to provide peaceful solutions to the crisis, which in turn escalates national-level tensions among a diversity of actors, including many within Chavismo ranks.

Worries surrounding the situation in Venezuela are not only linked to these dire circumstances but also to the language and discourse used by the Venezuelan government. While historically Chavismo has waved the flag of equality and inclusion, its discourse toward the opposition has been one of polarization, exclusion, and discrimination. In the context of escalating political, social, and economic conflict, the existence of entrenched discrimination based on the use of exclusionary ideology that constructs identities in terms of “us” and “them” is an alarming indicator for the international community. The risk of further repression and human rights violations is exacerbated with the common use of pejorative and discriminatory language and the deliberate tagging of opposition groups as terrorist and/or subversive organizations that are seeking to overthrow the government. If Latin American history in the 20th century can teach us an important lesson it is that when authoritarian regimes categorize opposition in broad terms such as “terrorists,” it is a precursor step toward the escalation of violence, increased repression, and likely justification of state-led atrocities.

Furthermore, Chavismo has been very effective in coopting state institutions, and those it cannot exert control over it has tried to outlaw, as was the case with the National Assembly in early 2017. This legislative branch of the government has been controlled by the opposition majority since January 2016, when parties opposing Chavismo won legislative elections by a landslide. Since then, the executive and judicial powers have systematically attempted to annul the National Assembly, overrule its decisions, and reduce its overall power.

In the meantime, President Nicolas Maduro, who carried forward his predecessor’s policies and ideology, has refused to hold a recall referendum to consult the population on whether he should continue in office, although the opposition has fulfilled all the steps required to call that referendum. He has also postponed regional elections, arguing that the dire economic situation makes it financially inviable. While he has proposed that a National Constituent Assembly draft a new constitution, the process has been handled in such a way that participants in the assembly are those sympathetic with Maduro’s government. It would also create a supraconstitutional power that would allow Chavismo politicians to fully concentrate power and overrule all opposition actions, which would contradict the 1999 Constitution.

The analysis of the Venezuelan crisis cannot be reduced to incidents inside the borders of the Caribbean state: its deepening humanitarian crisis is overflowing its borders as hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans leave, seeking better living conditions in neighboring countries. The main flow of emigrants has been toward Colombia, reversing the trend that lasted for decades of Colombians escaping their internal conflict and seeking refuge in Venezuela.

In the north of Brazil, the influx of Venezuelans has also increased exponentially, as people escape not only the severe shortages of food and medication but also the lawlessness of one of Venezuela’s most remote areas. A sanitary emergency has been declared in the Brazilian state of Roraima because the local health system is unable to cope with the massive arrival of Venezuelans. Brazilian Foreign Affairs Minister Aloysio Nunes has visited the expanding Venezuelan camps, and in February of this year, Dutch Foreign Affairs Minister Bert Koenders visited Aruba and Curacao and said those islands must remain “very alert” when it comes to the situation in neighboring Venezuela. In April he discussed preparing for increasing numbers of Venezuelan immigrants, including drafting a crisis plan that draws in contacts with the International Organization for Migration and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. At the same time, governmental concerns regarding the flow of Venezuelan refugees are rising in Panama and in Trinidad and Tobago off the coast.

The regional repercussions of the crisis are not only humanitarian but also commercial and political. Countries with deep-rooted economic ties to Venezuela are suffering the consequences of the acute recession there, reducing their exports and, in many cases, the import of cheap Venezuelan oil previously provided by Petrocaribe to maintain Venezuela´s regional network of political support. This network extended throughout the Caribbean and Central America, and it continues to be useful in stalling efforts by the Organization of American States (OAS) to apply the Inter-American Democratic Charter in Venezuela. Other regional organizations such as the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR) and the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States have proven unwilling or unable to bring about solutions, many times as a result of their support for the Venezuelan regime, which has molded their dialogue proposals into actions that have been interpreted by the Venezuelan opposition as lifelines for a dying regime.

While the regional community has been actively denouncing human rights violations and attempting to pass resolutions in the context of the OAS, these actions have had little to no impact on the decisions of the Venezuelan government.The attempt by the Vatican to support a dialogue initiative by three former presidents within the institutional context of UNASUR also failed to yield any results in late 2016. The regional and international strategy toward Venezuela may need to shift from purely “name and shame” to one aimed at exerting pressure on international actors that support the continuation of the Venezuelan regime, in addition to creating new spaces for domestic dialogue through a mechanism like a group of friends and using quiet diplomacy to engage Venezuelan officials and facilitate a process of democratic transition.

These diplomatic measures are particularly difficult tasks because of the existing political polarization and the reluctance of the Venezuelan government to accept any conditions to promote dialogue or a joint solution with the opposition. The fragility (or complete lack) of adequate institutional mechanisms to foster dialogue and compromise make it extremely difficult for any attempt to sort out the situation by identifying transitional forms of government that could lead to the reestablishment of governance or by identifying policies that can improve the situation for Venezuelan citizens.

Third parties that could act as facilitators or honest brokers in the process are mistrusted by both sides. As a result, it seems that if there is no possibility of developing some sort of dialogue with the most rational sectors of the parties in conflict, inevitably, some sort of external intervention will be required to stop the escalation of violence and the eventual bloodshed of a civil war. The pending question is: Are the international community in general and the United Nations in particular—after the previous failed attempts—willing to assume or capable of assuming responsibility and addressing the growing domestic crisis in Venezuela and its regional impact?